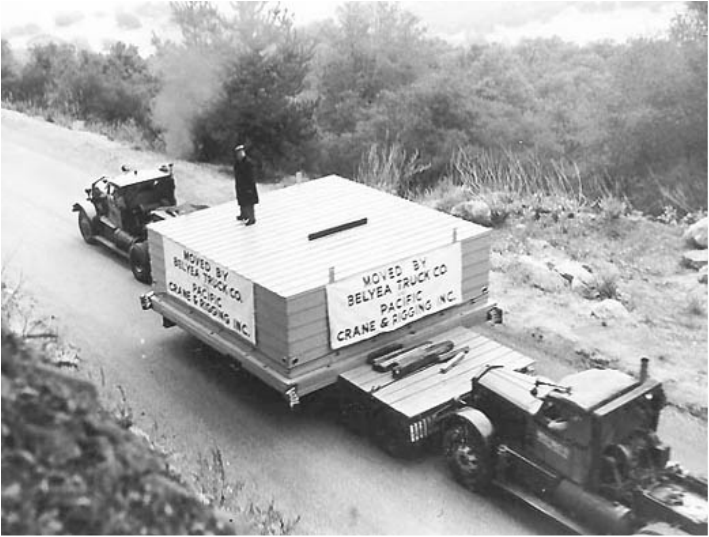

The transportation of the "Big Eye" lens to the Palomar Observatory

A Fruehauf Trailer hauls 60 tons in 1947

Palomar Astronomical Observatory is located in San Diego county, California in the Palomar Mountain Range. Conceived of by astronomer, George Ellery Hale, (1868-1938), and owned and operated by the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) research partners include the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and Cornell University. The observatory operates several telescopes, including the famous 200-inch (5.1 m) Hale Telescope. The history of the telescope’s creation and then installation captured the attention of the nation already absorbed by WWII. The 200-inch telescope was the most important telescope in the world from 1949 until 1992. Hale stated upon the completion of the historic installation,

"No method of advancing science is so productive as the development of new and more powerful instruments and methods of research. A larger telescope would not only furnish the necessary gain in light space-penetration and photographic resolving power, but permit the application of ideas and devices derived chiefly from the recent fundamental advances in physics and chemistry.”

Hale was correct in anticipating the great achievements of such a telescope. Astronomers using the Hale Telescope discovered quasars and gave us the first direct evidence of stars and asteroids in distant galaxies.

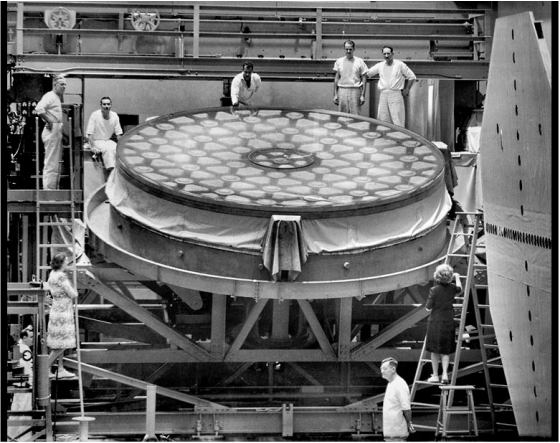

A delicate touch was needed to safely transport the country’s greatest imaging mirror from its place of production to its final destination. In 1934 the Corning Glass Works in New York State created the first primary mirror for the Hale telescope. They used their newest material called Pyrex (borosilicate glass), a product that possessed low expansion faculties that would not distort images when subjected to temperature variations. The mirror could not contain a single air bubble and had to be ground to two-millionths of an inch. The first attempt to cast the mirror failed when the mirror was ruined by the intense heat. The second attempt was successful. To assure perfection, the cooling process was slowed and took several months to complete.

"No method of advancing science is so productive as the development of new and more powerful instruments and methods of research. A larger telescope would not only furnish the necessary gain in light space-penetration and photographic resolving power, but permit the application of ideas and devices derived chiefly from the recent fundamental advances in physics and chemistry.”

Hale was correct in anticipating the great achievements of such a telescope. Astronomers using the Hale Telescope discovered quasars and gave us the first direct evidence of stars and asteroids in distant galaxies.

A delicate touch was needed to safely transport the country’s greatest imaging mirror from its place of production to its final destination. In 1934 the Corning Glass Works in New York State created the first primary mirror for the Hale telescope. They used their newest material called Pyrex (borosilicate glass), a product that possessed low expansion faculties that would not distort images when subjected to temperature variations. The mirror could not contain a single air bubble and had to be ground to two-millionths of an inch. The first attempt to cast the mirror failed when the mirror was ruined by the intense heat. The second attempt was successful. To assure perfection, the cooling process was slowed and took several months to complete.

Fruehauf announces the success

Fruehauf announces the success

In 1936, a train transported the specialized mirror to Caltech in Pasadena, California. An engineering achievement, the 20-foot circle was cushioned with foam rubber and asbestos to separate and protect it from damage by its metal case. There, scientists completed the painstaking engineering process of polishing, and adjusting for the historic Hale Telescope using a $6 million grant from the Rockefeller Foundation. In the optical shop in Pasadena, standard telescope mirror making techniques were used to turn the flat blank into a precise concave parabolic shape, although executed on a grand scale. A special 240-inch 25,000 lb mirror cell jig was constructed which could employ five different motions when the mirror was ground and polished. (1) Over 13 years almost 10,000 pounds of glass was ground and polished away reducing the weight of the mirror to 14.5 tons. The mirror was coated (and still is re-coated every 18–24 months) with a reflective aluminum surface using the same aluminum vacuum-deposition process invented in 1930 by Caltech physicist and astronomer John Strong. (2) The final design was perfected eleven years later in October 1947 and was later nicknamed the “Big Eye” by local enthusiasts and media. The sophisticated equipment was not only delicate but also enormous. This required specialized transportation to its intended destination at the Mount Palomar Observatory. A specially designed semi-trailer created by Fruehauf Trailer Company was employed to complete the task.

The biggest and most important scientific transport job to date was assigned to Jack Belyea and his company, Belyea Truck Company/Pacific Crane and Rigging, Inc., in November 1947. Belyea had become famous for successfully moving large objects. He and his brothers had a long history of transporting large objects that included a beached whale at Malibu, assorted yachts and a 148-foot girder. He once hauled a locomotive engine out of a canyon. He never turned down a hauling job. This job involved one of the most expensive and fragile objects that he would handle during his unusual career.

The biggest and most important scientific transport job to date was assigned to Jack Belyea and his company, Belyea Truck Company/Pacific Crane and Rigging, Inc., in November 1947. Belyea had become famous for successfully moving large objects. He and his brothers had a long history of transporting large objects that included a beached whale at Malibu, assorted yachts and a 148-foot girder. He once hauled a locomotive engine out of a canyon. He never turned down a hauling job. This job involved one of the most expensive and fragile objects that he would handle during his unusual career.

Belyea was well aware of the engineering skills and technology of the Fruehauf Trailer Company. Working with their team at Fruehauf’s Southern California location, his trailer was adapted and customized for his specialized heavy haul transport. He added additional I-beam support axles to his trailer, which were a Fruehauf patented design and hallmark of strength. Belyea arrived at Caltech with what he called his “Fruehauf jeep”, a dolly trailer with sixteen balloon tires. This Fruehauf trailer was Belyea’s most valuable piece of equipment. Using a 10-wheel Sterling diesel tractor-truck powered by a Cummins engine, the double gooseneck semi-trailer with 16 more wheels totaled 42 wheels making up the 79-foot long rig. The rig would measure 20 feet wide, twice the width of a standard highway lane and required the acquisition of numerous permits along the route. When finally loaded on to the trailer, the entire weight of the mirror and trailer was 60 tons. It took Belyea’s crew two days just to exit the shop’s 24-foot exit and 90-degree turn. The movers had only ¾ of an inch clearance on each side.

Belyea would travel foot-by-foot over the 160-mile route from Caltech in Pasadena to Palomar Observatory to prepare for the journey. Bridges were reinforced, special roads were built and others repaired to assure bump-free travel for the most valuable load ever transported. A crew would inspect the road every inch of the way during the journey. Radio crystal instruments would measure every movement during the anticipated two-day trip from Caltech to Palomar.

Belyea would travel foot-by-foot over the 160-mile route from Caltech in Pasadena to Palomar Observatory to prepare for the journey. Bridges were reinforced, special roads were built and others repaired to assure bump-free travel for the most valuable load ever transported. A crew would inspect the road every inch of the way during the journey. Radio crystal instruments would measure every movement during the anticipated two-day trip from Caltech to Palomar.

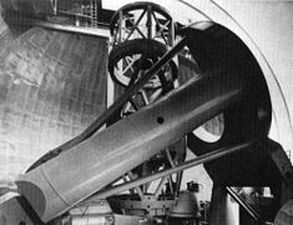

The Hale Telescope at the Palomar Observatory

The Hale Telescope at the Palomar Observatory

The convoy departed on Sunday, November 16, 1947. Armed guards, police and California Highway Patrol accompanied the transport to guarantee no outside intrusion by unwanted traffic. The exact dates were kept secret as some members of the public viewed the installation of the telescope as controversial.

The transport progressed a foot at a time, and fuel averaged three miles to a gallon. The truck was refueled on-the-go. Besides the Sterling that pulled the Fruehauf trailer, two additional Sterlings assisted by carrying supplies as well as pushing the rig up the steeper grades, like tug boats.

After a tedious three day journey, the caravan arrived at Palomar Wednesday, November 19, 1947. Upon arrival, the semi-trailer was disconnected from the tractor in order to get through doorways of the Caltech storage facility. Other doorways were demolished to accommodate the width and complete installation. Another two years was needed for further refinements, polishing and adjustments until the telescope could be put into use. One of the first astronomers to use the Hale telescope was Edwin Powell Hubble (1889–1953).

On March 8, 1948 Time Magazine printed an interesting Fruehauf advertisement on page 109. “Palomar’s famous mirror is hauled on a Fruehauf.” A Fruehauf trailer had safely transported the 200-inch disk from Pasadena, California to its final home at Mount Palomar Observatory.

“Truck-trailer transport has hauled successfully the biggest reflecting mirror ever formed. This was the hauling job that climaxed all hauling jobs to date.”

The Fruehauf Trailer Company again makes history.

The transport progressed a foot at a time, and fuel averaged three miles to a gallon. The truck was refueled on-the-go. Besides the Sterling that pulled the Fruehauf trailer, two additional Sterlings assisted by carrying supplies as well as pushing the rig up the steeper grades, like tug boats.

After a tedious three day journey, the caravan arrived at Palomar Wednesday, November 19, 1947. Upon arrival, the semi-trailer was disconnected from the tractor in order to get through doorways of the Caltech storage facility. Other doorways were demolished to accommodate the width and complete installation. Another two years was needed for further refinements, polishing and adjustments until the telescope could be put into use. One of the first astronomers to use the Hale telescope was Edwin Powell Hubble (1889–1953).

On March 8, 1948 Time Magazine printed an interesting Fruehauf advertisement on page 109. “Palomar’s famous mirror is hauled on a Fruehauf.” A Fruehauf trailer had safely transported the 200-inch disk from Pasadena, California to its final home at Mount Palomar Observatory.

“Truck-trailer transport has hauled successfully the biggest reflecting mirror ever formed. This was the hauling job that climaxed all hauling jobs to date.”

The Fruehauf Trailer Company again makes history.

1. "Grinder With Human Touch to Polish Eye for Telescope" Popular Mechanics, April 1936 bottom of pg 566

2. "Mirror, Mirror: Keeping the Hale Telescope optically sharp" by Jim Destefani, Products Finishing Magazine, 2008

2. "Mirror, Mirror: Keeping the Hale Telescope optically sharp" by Jim Destefani, Products Finishing Magazine, 2008